Alan Weisman

Over the course of the past one hundred years, we humans have grown in population at a rate rarely seen outside of a petri dish. Alan Weisman, author of the best-selling The World Without Us, spent two years traveling to twenty nations to investigate what this population explosion means for our species as well as those we share the planet with—and, most importantly, what we can do about it. His latest book is Countdown: Our Last, Best Hope for a Future on Earth? Orion magazine editor Andrew D. Blechman met with Alan at his home in rural Massachusetts, amid birdsong and the patter of rainfall, to discuss some of the most serious issues ever to face the human species.

Andrew Blechman: Population is perhaps the monumental topic of our time, and yet the title of your book ends in a question mark. Why is that?

Alan Weisman: I’m a journalist, not an activist. I don’t make statements, but I try to find the answers to big, burning questions. This is the big one to me, because it addresses whether we’ll be able to continue as a species, given all the things that we have been doing to our home.

Andrew: The human population stayed relatively stable, or grew at a manageable rate, for tens of thousands of years but exploded in the past century. What happened? How did we humans come to dominate the planet so quickly?

Alan: The explosion began during the Industrial Revolution. Jobs were suddenly in cities rather than on farms. People were living in tight quarters, and that became an incentive for doctors to begin dealing with diseases that were starting to spread much more easily. Beginning with the nineteenth century, medical advances, such as the smallpox vaccination, were either eradicating diseases or controlling the pests that spread diseases. Suddenly, people were living longer, fewer infants were dying.

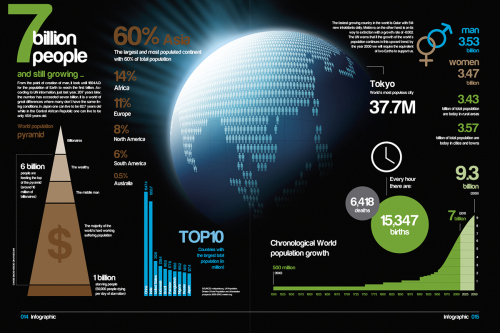

7 billion people and rising (click for full size graphic). Courtesy of Infographic List: http://infographiclist.com/2012/03/21/7-billion-people-and-still-growing-infographic/

Andrew: Before that, we were basically at a replacement rate?

Alan: Pretty much. Women would have seven or eight kids, and if they were lucky, two survived. Two is replacement rate. If a male and female have two kids, then they have essentially replaced themselves. Population remained stable because as many people were dying as were being born.

The other thing was that suddenly we learned how to produce far more food than nature could ever do on its own. Nature’s ability to produce plant life has always been limited by the amount of nitrogen that bacteria could pull out of the air and provide as food for plants. In the twentieth century, we discovered how to pull nitrogen out of the air artificially. As a result, we suddenly came up with artificial fertilizer that could produce much more plant life on this planet than had ever existed before. We were at about 2 billion in 1930 when we started using artificial nitrogen extensively. Today we’re at 7 billion. Between 40 and 50 percent of us would not be alive without artificial nitrogen fertilizer. It nearly doubled the food supply.

Andrew: They say that, in some ways, too much abundance isn’t actually good for a population, that it can actually stress it because it leads to overpopulation. For example, if you overfeed city pigeons, they have more babies and the population starts maxing out, whereas if you don’t overfeed them, the population keeps itself in check.

Alan: That’s the paradox of food production—it can ultimately undermine the viability of a population. At a certain point, it expands beyond its resource base, and then it crashes. Wildlife managers, for example, well know that if we don’t keep population in balance with food, a species can run into serious problems. They know that they can either relax controls on natural predators, or issue more permits to hunters—that is, human predators.

Andrew: What does it mean for the Earth to be full? For example, 350 parts per million has been identified as the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere beyond which we set in motion changes that will threaten the future of life as we know it. Is there a comparable figure for global population numbers?

Alan: That was one of the big questions that I set out to answer, or to try to see if it’s possible to answer: how many people can fit on the planet without tipping it over? It’s completely related to what we are doing. If we all lived an agrarian life, self-limitations would set in and our numbers wouldn’t grow much beyond our ability to grow our own food. However, if we are force-feeding our crops through chemistry, we can produce a lot more food, and a lot more of us, too. At a certain point, a downside kicks in to that.

But the answer to your question isn’t really known because we’re finding it out right now. We’re all part of a big experiment to see how many of us can live on this planet without doing something to it that is going to destabilize it so much that our own future is in jeopardy.

Andrew: Isn’t it almost impossible to predict the future, given how variables change? What if the population problem is self-correcting? After all, we’re no longer doubling, and many developed nations are experiencing population decline.

Alan: Some argue that population is in fact self-correcting, and that the correction is already underway. But it’s a little like saying a house fire is self-correcting, because it will eventually put itself out. Unfortunately the damage is done. One way or another, when a species exceeds its resource base, the population will come down. Nature does that in 100% of the cases in the history of biology. The question that I keep coming back to is, how soon is that going to happen?

Andrew: And will it be in time?

Alan: Exactly. If our population is coming down because nature is going to do it for us, well, it’s going to be, frankly, unpleasant to watch. When nature does in a horde of locusts because they eat themselves out of sustenance, it’s interesting for us to observe. When it happens to our own species, it’s not going to be very pretty.

So Many new consumers in Shanghai. Photo by Austronesian.

Andrew: Is it the sheer number of people or is it the amount that we consume that matters, particularly in the so-called developed nations. Or is it simply that we live too long?

Alan: The answer to all of that is yes. All of those things are involved. I’m always curious about what people are thinking when they say, “It’s not population; it’s consumption.” Who do they think is doing all the consuming? The more consumers there are, consuming too much, the more consumption.

Andrew: And, as you mention in your book, there’s no condom for consumption.

Alan: I think, in the twentieth century, when our population quadrupled, we got to the point where we kind of redefined original sin. Just by being born, we’re part of the problem. There’s also no question that the most overpopulated country on Earth is actually the United States, because we consume at such a ferocious rate. We may not be as numerous as China or as India, but our total impact is huge.

That doesn’t mean that poor people in developing nations don’t have a severe impact on the environment. I was in Niger, which has the highest fertility rate on the planet now. Its average is around eight children per fertile female. In every village, I heard, “Had you been here twenty-five years ago, you couldn’t have seen that house over there for all the trees that we used to have.” Where did the trees go? Well, they needed them for firewood, and then the climate began changing and there’s less rain now. They’re not responsible for the industrial pollution that has gunked up the atmosphere, but when you take down trees, things change. You graze too many animals, and things really change. They’re now in chronic drought. In every village, hundreds of children have died.

What will ultimately carry the day in Niger is the dawning realization that they don’t have the luxury of continuing life as they used to live it, where men had multiple wives and wives had many children. And it’s not just in Niger, but many countries on the planet. Education seems to be the key. Any time you start to educate people, they start to put these things together, particularly if you educate women. Education is the best contraceptive of all.

The more you educate women, the faster the birth rate drops. Photo courtesy of Development Diaries: http://developmentdiaries.com/ethiopia-angola-double-number-of-girls-in-school-in-10-years/

Andrew: That’s what I gather from your book—the more you educate women, the faster the birth rate drops, and the quicker a population adopts a family-planning mentality.

Alan: It was one of the wonderful things about doing this book, which could otherwise have been very grim and sobering. I went to so many countries, twenty-one including all my travels around the United States. I saw human beings confronting some of the most difficult questions in our history. How are we going to survive? What are we doing to ourselves? Yet one of the easiest things that we can do that can make such a huge difference is one of these blessed win-win situations. You educate women, and give women rights that are equal to anybody else’s on this planet, and they generally choose to have fewer children, because they have another way to contribute to society that would be difficult if they had seven kids to care for.

Every place where you’ve got really educated women, you’ve got a society that is more and more livable. The more women decision makers we have, the better our chances. All we have to do is offer fair, equal opportunity to half the human race, the female half. This problem will start taking care of itself really, really quickly. A whole lot of environmental problems, within a couple generations, will also ease up because there’ll be a lot more space on this planet for other species.

Andrew: It’s amazing how flexible we can be as a species. Humans seem to adapt to having large families, and they seem to adapt just as easily to having very small families, even single children.

Alan: There’s a moment in the book with four hundred brilliant, animated students at Guangzhou University in China. Their parents or grandparents had been denied education in the Cultural Revolution and led limited lives. But these Chinese kids believe the twenty-first century is theirs. They’ve got education and incredible opportunities to do interesting work. The sky is the limit for them—but also literally, because they know that Guangzhou’s factory pollution hangs over their lives, and that it would be even worse if China hadn’t curbed its population.

Something occurred to me out of the blue. I asked my translator, a young woman in her twenties, “Hey, are they all only children?” She said, “Sure. We all are.”

Many people appalled by China’s one-child policy think it must be so unnatural not to have siblings. I asked these kids whether they missed having siblings. They admitted that yes, they did. But then they said, “On the other hand, our cousins have become our siblings. Sometimes our best friends have. We’ve reinvented the family.”

That, to me, was yet another example of the great flexibility of the human race, that we can make adjustments when we need to.

Andrew: Now that it’s entered its fourth decade, what other lessons can we learn from China’s massive social experiment with the one-child policy?

Alan: In one sense, the one-child policy has been successful—there would be 400 million more Chinese otherwise. And we’ve learned valuable lessons about population management, like the threat of discrimination, even lethal, against female babies.

We’ve also learned that while a draconian edict may have worked in one place, it’s not going to work everywhere. We have to take the culture of a country, a nation, a political system, a religious system, into account if we’re going to talk about managing population, which I think we have to do. Look, if we manage populations of predators and prey in parks because they have limits, we need to realize that we’ve now come to the limits of our planet. We occupy the whole thing—in a sense the Earth is now a park, it’s parkland. We live in it, and we have to manage it ourselves. There’s no way around that. Sure, maybe we can learn to consume less. But frankly, if we try to attack consumption to solve all of our problems, by the time we change human nature enough so that people consume a lot less, I think the Earth will be trashed in the meantime. So I think there are other things we have to do.

Andrew: It seems like contraception is a lot easier to encourage.

Alan: Yes, and it’s improving enormously. We’re no longer overloading women with estrogen the way that we used to. Even better, there are several male contraceptives that are becoming available that involve much simpler chemistry.

Andrew: As you’ve said, restricting the size of families through legislation is usually viewed with disdain. After all, for many, children represent hope, the future incarnate, and reproduction a fundamental human right, even a biological imperative. But can we really tackle global population without resorting to this sort of intervention?

Alan: I don’t think we need to legislate population management. What we need to do is make it very attractive to people, and let them manage their own population. I’ve got several examples in this book, big examples, of where this has worked brilliantly. There are a couple of Muslim nations that I refer to that have brought their populations down to replacement levels without draconian controls from above, without any edicts. They’ve done it through making family planning available, and making it available for free in one case, and also opening up the universities to women and encouraging them to get educated.

Andrew: Like Iran.

Alan: Like Iran, yes. Iran is the place that has had the most successful family-planning program in the history of the planet. They got down to replacement rate a year faster than China, and it was completely voluntary. The only thing that was obligatory in Iran was premarital counseling, which is actually a very nice idea. You could go to a mosque, or you could just go to a health center. They would talk about things to get you prepared for getting married, including what it costs to have a child, to raise a child, to educate a child.

Andrew: It’s interesting to hear about such a program being embraced by a theocracy. Do the world’s major religions generally differ when it comes to family planning, or do they share similar beliefs?

Alan: The Catholic Church is somewhat unique in its adamant opposition to birth control. Unless it’s the rhythm method, so-called natural methods of determining when to have sex that might lead to procreation or not, it’s simply unacceptable.

I went to the Vatican for my book. It’s a very curious place. It’s the smallest country on Earth, only 110 acres, and populated by just 1,000 people, virtually all of them old men. They’re making these rules that many Catholics outside its walls are paying no attention to. Italy and Spain, for example, have two of the lowest birth rates on the planet. That’s because women are using contraception.

Other religions argue within themselves on these issues. You find conflicting opinions in all three of the major monotheistic religions. In Evangelical Christianity in the United States, there has been an anti-abortion, even anti-contraception movement that’s very strident, restricting women’s access to the birth control of their choice. Yet I interviewed an Evangelical leader who absolutely supports contraception and campaigns hard for it. They’re citing the same Bible.

Andrew: When it comes to protecting species, how many can we save? Are we at the “Sophie’s Choice” moment of being forced to choose?

Alan: We really don’t know. We know that the extinction rate is accelerating very fast as our presence on this planet pushes other species off the edge. At a certain point, potentially, we could push something off the planet that we won’t know that we needed until it’s too late. There is a terrible dilemma for ecologists, particularly conservation biologists, who are trying to conserve enough biology to keep ecosystems viable, and that includes viable for Homo sapiens. We’re just another species in that ecosystem. It’s hard for them to know which ones to save. How do we decide? Could we even control it if we knew which ones?

Say there is a species out there that we depend on; let’s say for food. Everything we eat is the sum total of everything that it ate, and all the things that these things ate before they were eaten. We use the phrase “food chain” but that’s not really descriptive. Pretty much every animal species on land has to consume ten times its weight of other terrestrial species, including plant life, because only about 10% of what we consume converts to body mass. That means that everything that we eat has eaten ten times its weight. We’re at the apex of a very large pyramid. When you lose a species, or more than one, the whole pyramid starts to crumble.

For this book, I wanted to see how we might establish a more harmonious relationship with our species and the rest of nature, as opposed to the mortal combat that we find ourselves in. I wanted to know what the happy medium is, if there is one, a happy medium between a world without us and the one with us, which we’re currently overwhelming. When I started to look at what we are doing—the numbers were so boggling. I did some long division to make it more understandable. It came down to every four to four-and-a-half days, there’s a million more of us on the planet. That just doesn’t seem like a sustainable figure, and that’s pretty much where we are unless we start to do something about it.

Interestingly, some wildlife ecologists have started taking family planning into their own hands. In Uganda, for example, the country’s fabulous biodiversity, such as its gorillas, which tourists are willing to spend a lot of money to see, is getting chipped away by an unmitigated human population explosion. The ecologists began to realize that in order to preserve the wildlife, as well as the tourist-related income for the people who live in these areas, they needed to convince residents to have fewer children.

Andrew: What about the other side of the population coin? If you look at the European democracies, their birthrates are so low that they’ve resorted to paying their citizens to have children. For them, among other concerns, it’s about economics. How are economies such as theirs going to cope with shrinking populations? It seems like calibrating or recalibrating such a thing—trying to mesh just the right amount of people with just the right amount of economy—is a tough thing to do.

Alan: It’s a tremendously tough thing to do. We’ve never had to do it before. We’ve always had room to expand, or thought we had room to expand, until it turns out we were encroaching on other things that were really important to us. China kept expanding by just knocking down more and more forests, and then suddenly, they lost all their flood control. Now they’re trying to put the forests back.

We’ve never had to manage our population before, and our economies were always a reflection of our natural increase. All of our conventional determining factors for the health of the economy regard whether it’s growing. Bill Clinton even turned economic growth into a transitive verb—We have to ‘grow’ the economy—as if we were planting seeds and watering them.

It turns out that population growth and economic growth is inextricable. For an economy to keep growing, you have to have growing populations, because you need more laborers to produce more products, and then you need more consumers for those products.

If we have to start limiting our population, then we’re going to have to come up with a way to redefine prosperity that doesn’t involve perpetual growth. A shrinking population or a stable population can’t be a perpetual-growth society.

Andrew: How will countries with declining populations care for all of their elderly?

Alan: It’s an oft-repeated fear that circulates in the business and economic world out there that an aging population is terrible for the world, because there’ll be all these unproductive people and there won’t be enough productive young people paying into the social welfare coffers to take care of them.

Yes, some countries have shrinking populations. But they’re not looking at a situation that goes on into perpetuity, in which they have far more older people than younger people. They’re looking at a generation or so of a bubble where they’re going to have more older people, and then, as that generation dies off, the number of older people and younger people are going to balance out again, and it’s not going to be a problem.

How do they economically get through those bubble years? As an American, I can think of an awful lot of things that my government is spending money on right now that if it dedicated those monies to taking care of a generation of older people until our population evened out, we’d be a much better society.

Andrew: I was really surprised by the fact that the future of the planet, in many ways, rests on whether women on average have a half child more or a half child less.

Alan: Those are pretty shocking numbers, and I got them from a couple of different demographers. By the middle of the century, our population will be nearly 10 billion. But that assumes that all the family planning programs we have in place will remain in place. And it’s a pretty fragile network, dependent on a few donor countries, the most important one being the United States. Had the last presidential election gone differently, the United States may well have withdrawn a great deal of its support for family planning programs all over the world.

If family planning does not keep up with our population growth, or, if suddenly, for whatever reason, the supply lines break down and birth control pills or whatever contraception they’re using is not available to women in a lot of places around the world, a half a child more per fertile woman means that by the end of the century we’re going to increase to 16 billion people. A half a child less per woman means that we’re going to be back down to 6 billion really quickly. Then we can decide at that point if we want to bring it down further. But the difference is, on average, half a child either way.

Andrew: As a species, we seem somehow hard-wired to have difficulty seeing beyond our immediate surroundings or thinking beyond the short term. If that’s the case, what do you think motivates humans to change their ways? What do you think is going to work in this instance? How do you convince a species to rein itself in?

Alan: If we could convince people that it’s in their own best interest to limit the number of children they have—to limit the size of their families—then we’ve got a fighting chance.

It turns out that having fewer kids helps virtually every family. You see billboards in countries all over the world—they’re kind of clichés at this point—with a woman surrounded by thirteen ragged children. Then you see a couple with only two kids, and they’re all dressed well. Everybody looks healthy. People get that message pretty quickly.

Andrew: After researching this topic so intensely, what gives you the most hope?

Alan: The fact that there is something so sensible, so wonderful, and with so many benefits that can alleviate the pressures that we human beings put on this planet and improve our own existence as humans-and that’s simply educating women.

If we give women all the opportunities that they deserve, they’re going to take care of this problem, and frankly, we’d have a much better society all the way around. That goes for any religion. That goes for any culture that I’ve ever visited. Any place where you run into women who are empowered, things improve. Everybody lives better, males and females. Women who are educated are going to have fewer children, and that gives me a great deal of hope.

In addition to that, making birth control available on a global level is also very doable. We’re not there yet in terms of distribution—nearly a quarter of a billion women who might use contraception don’t have access to it. However, it would only take about $8-9 billion a year to ensure that everybody did. It’s just not a lot of money on this planet, and it would have such a wonderful, multifaceted impact. We’d have fewer unwanted children. We’d have fewer abortions. We’d have happier people.

Best of all, none of this involves high technology. This does not involve coming up with renewable energy—given all of our best efforts, we still don’t know how to power all of our vehicles and all of our industries with just the sun or wind. This is technology that we already have. In fact, the education part of it employs the best of human technology—our own brains—to convey information and wisdom to our children. Those young brains can absorb it all, and get very creative with it, and do amazing things, as human beings are capable of doing.

Source: Orion magazine <http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/7694> Reprinted with permission. Orion is an award-winning, non-profit, and ad-free publication. Anyone can request a free copy by going to <www.orionmagazine.org/freetrial>. Or you may subscribe for just $19 for 6 issues, nearly half off. An audio recording of the complete interview of Alan Weisman by Andrew Blechman is available at <www.orionmagazine.org/audio-video>.